4th July 1919 – 12th July 1991

My father was born on July 4th, 1919. The circumstances of his birth will be the most engaging part of this entire family history project, since the whole concept of a family tree might be restricted by my lack of knowledge of his origins, and my paternal genetic ancestry.

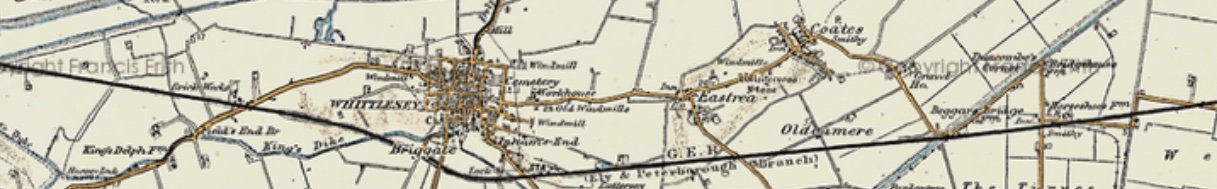

His family lived in a small village called Coates, near a slightly larger village called Whittlesey, about 4 miles east of Peterborough, on the western edge of the Fens. We think the name Willimer evolved from the common Dutch-German family name of Wilmer. There were two waves of emigration from the Low Countires to England in the Middle Ages. In the 12th Century, many Dutch farmers were displaced by major flooding in Zeeland and Holland and migrated to the area around The Wash. Then, in the late 16th century, hundreds of thousands of Huguenots fled religious persecution of Protestants in France, Belgium and Holland, settling in East Anglia which was known to be tolerant of religious differences.

I can’t begin my fathers’ story without immediately raising the mystery surrounding his birth. He was brought up alongside four people who he believed were his siblings. But he later discovered that the three men he knew as brothers were his uncles, and the older sister he called Rose was actually his mother. I remember Granny Goby, and as a child I obviously had no inkling of her role in this unusual backstory. But the stories Dad told me of his life in the Fens made more sense when I eventually learned of his upbringing.

Dad enlisted in the Royal Air Force in November 1939, shortly after the beginning of hostilities in World War II. He was barely eighteen years old, and was initially training as a batman – a kind of valet-cum-servant – to a senior officer. But at some point, he began training as an armourer for heavy bombers, working on Wellingtons and Lancasters. I have his warrant card which recorded his movements from base to base. He was posted to Hereford, Desborough and Cottesmore among other places, but crucially he spent the first four years of the war at RAF Bassingbourn, just a few miles from Royston.

I don’t know much about their courtship, but it’s not hard to imagine how he met my mum. War time dances, dashing young men in their blue uniforms at local dances – we’ve all seen those movies. I know they spent time together on Royston Heath, because many years later both their ashes were spread there, on their favourite spot. They married in October 1941, and had two children before the war ended, four years later. From their stories, I know wartime was hard – the separation, Dad traveling home on a 48 hour pass from distant stations, and mum having to endure a cruel stepmother while caring for her two young children.

Dad attained the rank of Leading Aircraftsman (LAC), and on 3rd December 1945, 908363 LAC Willimer was finally discharged from the RAF. After the war, the new Labour government made great strides to improve the lot of the population who had given so much for victory. There was very low unemployment, a new National Health Service providing free healthcare, and National Insurance to fund welfare benefits, including unemployment and sickness pay, and pensions. Housing was more problematic, and it took longer to address the shortfall in housing stock.

But in 1948, Mum and Dad moved into a brand new council house at 10 Orchard Way, which became the family home for 37 years. My brother Nigel was born in this house, and it was my home for the first 18 years of my life. Dad became a house painter, and worked for several local builders before he formed a partnership with Cyril Wing and they went into business for themselves. I remember the paraphenalia of that job in our outhouses, paint cans, brushes and heavy, heavy drop cloths – and the almost constant smell of paint. During the school holidays, if cleaning work was available, Mum and I would sometimes accompany him to some big new housing estate in the local villages, where the houses smelled of plaster, sawdust, and the tang of white gloss paint on new windows. Their business partnership fell apart acrimoniously – my understanding was that money put aside for tax and national insurance had somehow not made its way to the taxman, and they had to deal with a sizeable outstanding balance.

After that, Dad gave up painting, and took a steadier job working at Johnson Matthey, a large local chemical factory. When I later worked at the same place one summer, I realised that his job had been pretty menial, and involved cleaning the mess room and making tea for the other workers. By then he had retired, so my feeling of discomfort on his behalf was lessened. He had actually been forced to retire after being diagnosed with platinosis, a dangerous allergic reaction to platinum products, and an occupational hazard that befell many workers at JM. This dismissal was accompanied by a reasonable settlement that meant he no longer had to work – just as well, as he was now in his 60s, and his health was declining.

In 1985, Mum and Dad moved from Orchard Way to a sheltered flat in a brand new development in the centre of Royston. The flat was small, but it was a perfect step for them. They became the focus of activities in Kings House, and had a fairly constant stream of visitors – both family, and friends who they reconnected with. They were settled, and seemed very happy.

Then over Christmas in 1988 (I think), Dad had his first heart attack. Apart from the platinosis, Dad had been a smoker all his life, probably from his teenage years, and this had affected his circulation. I was on a trip to Australia when it happened. My then-partner Sarah and I were staying with her parents in Perth, and I can remember being very confused when the phone rang, and Sarah’s mother said “It’s for you”. Doug, my brother-in-law, relayed the news as we tried to make sense of the time zones. Dad was ill, but being cared for. I couldn’t get there quickly even if I tried, so I didn’t. That trip was strange for many reasons, and the uncertainty of what was happening thousands of miles away added to my feeling of otherworldliness.

Sarah and I parted within a year, and I moved to London. I regularly drove up to Royston see them both, often driving back down the M11 and across South London in the early hours. Dad was obviously taking it easy, though his legs remained a problem. And then, in 1991, not long after his birthday, he had another heart attack. He was not expected to survive this time, and Mum insisted on caring for him in their little flat. She slept in the bed with him, and woke up one morning to find him silent and peaceful beside her. I had been there the previous evening and driven back to London, so I was on my way into work when Nigel called. I still remember the enormity of our conversation, conveyed in so few words.

“Chris ? It’s Nigel. He’s gone.”

“OK. I’m on my way.”

Dad was cremated, and Mum spread his ashes on Royston Heath. Some years later, she took me to the Heath and pointed out a single tree, sited where paths converged from several directions, and offering a panoramic view to the north west, over the flat, peaceful farmland of South Cambridgeshire. It was easy to imagine many young lovers sitting here over the years, making plans.

“That’s our tree…” she said, “that’s where I want my ashes to go.”

When he died, they were just a few months short of their Golden Wedding anniversary, a milestone which had meant a lot to him. He’d written a poem for Mum for a birthday which referred to their ‘years of gold’, which she framed and kept on top of her TV for many, many years. Considering how few marriages last that long, it’s fair to say that most of those fifty years were worth their weight in gold.

Leave a Reply